The growing prospects of Nigeria’s total public debt rising to about N68.58 trillion in the first quarter of 2023 has necessitated a call for the establishment of a Debt Performance Auditing Mechanism to track and curb the country’s rising debts, a report by the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC) has recommended.

On December 9, 2022, the Debt Management Office (DMO) gave the country’s total public debt as N44.06 trillion. This comprised of total domestic debt of N26.92 trillion, and external debt stock of N17.15 trillion of the Federal and State government as well as the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja.

When the additional N819.5 billion borrowing in the 2022 Supplementary Appropriation Bill approved by the Senate last Wednesday is added, the figure comes to N44.88 trillion.

Again, a request by President Muhammadu Buhari for the approval of another N23.7 trillion is already before the National Assembly pending their resumption from Christmas break on January 17, 2023.

The amount represents the total advances the Federal Government got from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) through Ways & Means, which has already been spent on the implementation of projects and programmes as a result of the fiscal deficits in the Federal budgets since the Buhari administration came to office in 2015.

When the request is approved, the country’s total debt is expected to rise to N68.58 trillion, out of which the Buhari administration would account for over N55.7 trillion debt over the last seven years, or 81.23 percent of the total portfolio.

Speaking at the presentation of a report entitled: “The Role of Private Creditors in Nigeria’s Debt Crisis and Its Human Costs”, the Executive Director of CISLAC, Auwal Ibrahim Musa (Rafsanjani), said Nigeria appears headed for a debt crisis, with limited access to further financing on concessional terms, as a result of the negative influence of private creditors.

Musa said the rising debt profile was increasingly putting the country in a precarious situation, with significant implications for human rights, including to education, health, and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

“A growing proportion of external debts owed to private creditors under opaque terms and often subject to high-interest rates is contributing to spiraling debt servicing costs, increasing the risks to Nigeria’s economy,” he said.

“This trend is playing out in a context of lack of transparency in lending more generally, which is a barrier to holding governments accountable for debts they incur – alongside the deep economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated fiscal constraints,” he added.

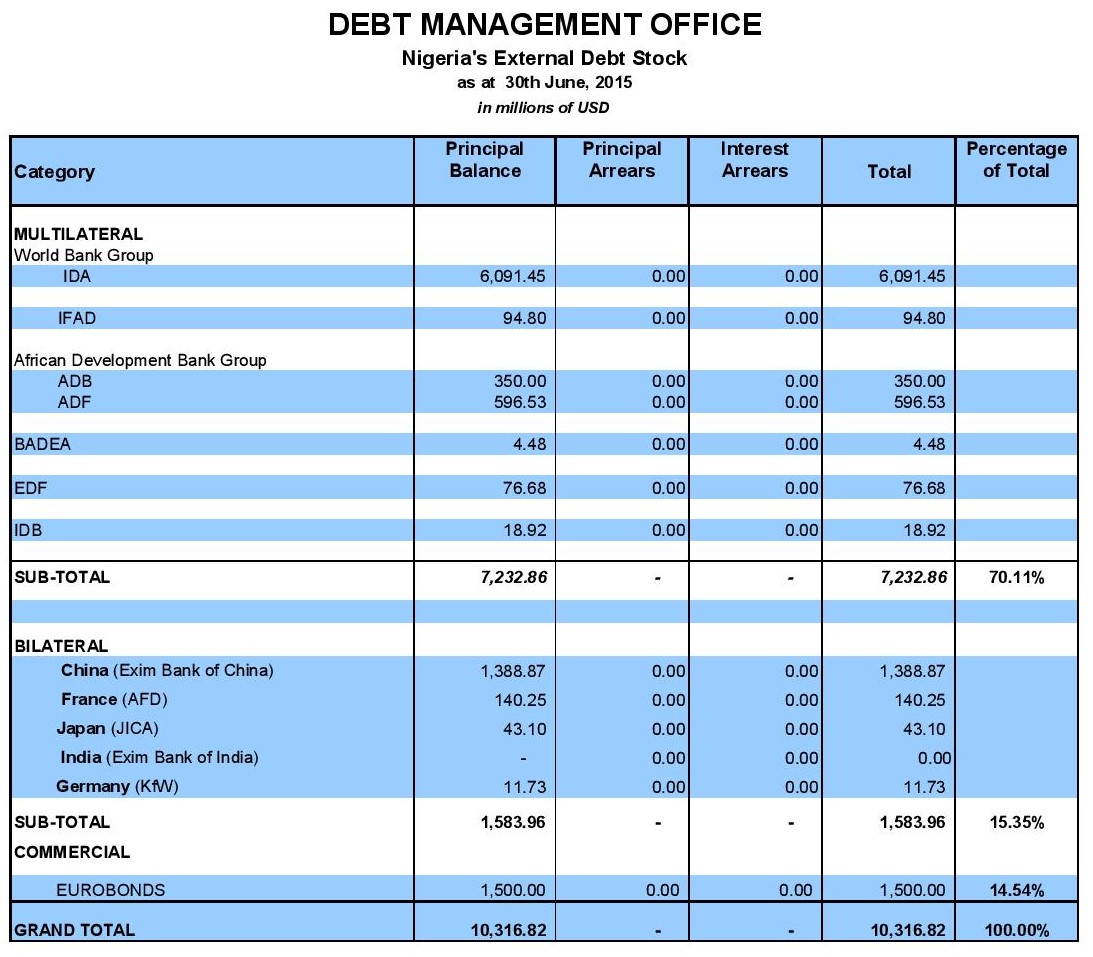

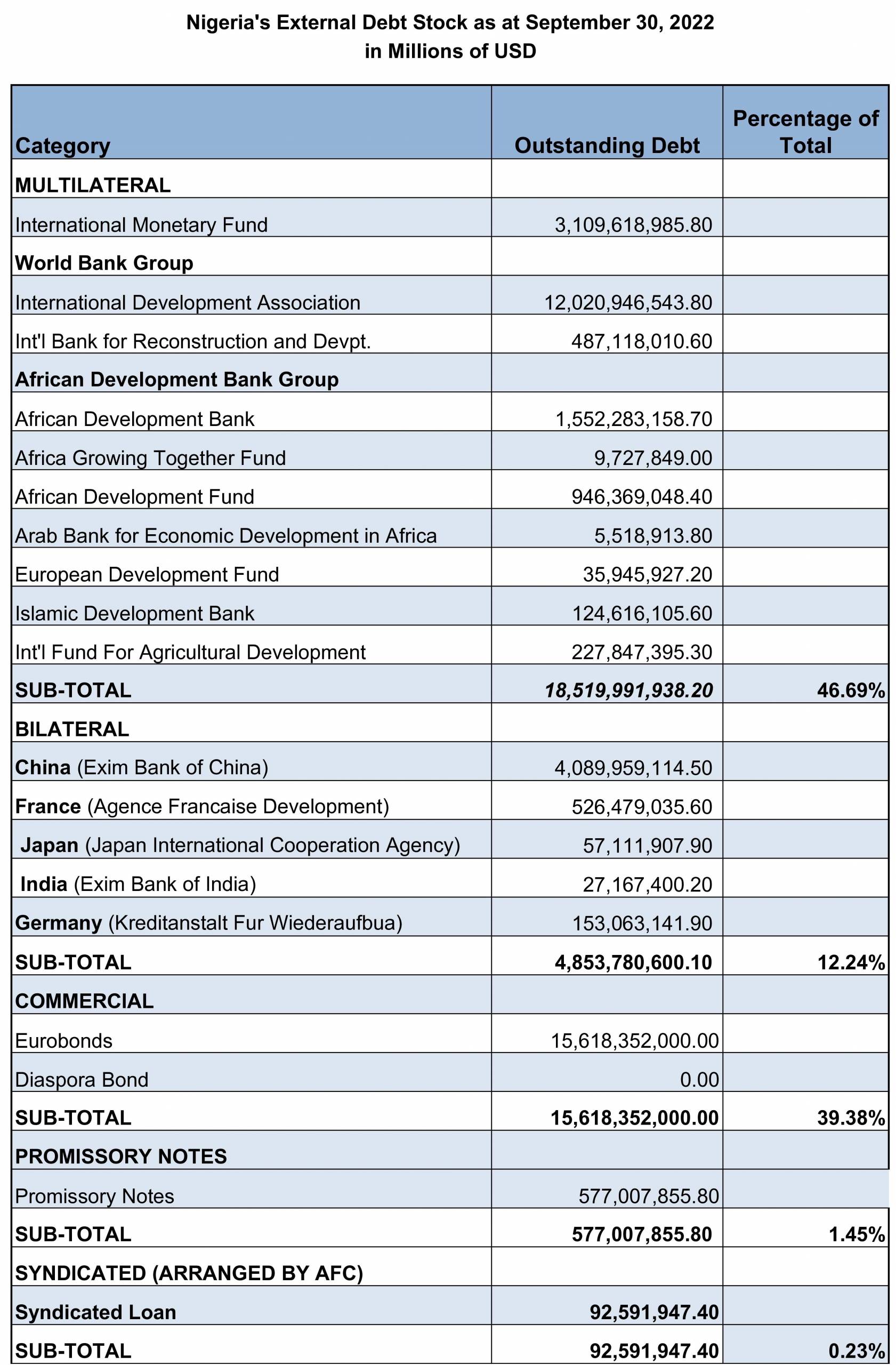

A review of the debt stock showed that the country’s total external debt of $10.32 billion as of June 30, 2015, inherited by the Buhari administration, has risen to $39.7 billion as of September 30, 2022.

Details showed that the debt to Multilateral financial institutions under the World Bank Group and the African Development Bank Group, which stood at $7.23 billion as of June 30, 2015account and account for 70.11 percent of the total debt, rose to over $18.52 billion as of September 30, 2022, representing 46.69 percent of the total debt.

The Multilateral institutions include the International Development Association (IDA), International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), African Development Bank, Africa Growing Together Fund, African Development Fund, Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa, European Development Fund, Islamic Development Bank, and International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Over the corresponding period, debt to financial institutions affiliated with Bilateral organizations was about $1.58 billion, or 15.35 percent of the total, rose to $4.85 billion, or 12.24 percent. They include the Chinese Export-Import Bank, France’s Agence Francaise Development Bank, Japan International Cooperation Agency, India’s Export-Import Bank, and Germany’s Kreditanstalt Fur Wiederaufbua.

The Commercial debt incurred through the issuance of Eurobonds, which stood at $1.5 billion and constituted 14.54 percent of the total debt as of June 30, 2015, grew to $15.62 billion, or 39.38 percent of the total, while Promissory Notes was $577.01 million, or 1.45 percent, and syndicated loan arranged by the African Finance Corporation (AFC) was about $92.6 million, or 0.23 percent as of September 30, 2022.

The report prepared by CISLAC Transparency International Nigeria, with funding by Funders Organize for Rights in the Global Economy (FORGE) and Christian Aid Nigeria, identified a major contributor to the rising public debt to the unprecedented influx of private lenders looking for higher returns outside advanced economies following the global financial crisis of 2018.

CISLAC noted that the past decade, which witnessed the largest, fastest and most broad-based increase in debt in emerging and developing countries over the past 50 years, saw the total debt of these economies in these economies climbing by about 54 percentage points of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to a historic peak of almost 170 percent of GDP in 2018.

Findings from the report showed that Nigeria’s public debt appears headed for a major crisis, as the country’s sovereign debt reached an all-time high level of over $100 billion, with its external component currently at over 1,333 percent in the last seven years as a result of unfavourable borrowing terms.

The report said debt servicing has become a significant burden on the country’s economy, involving about 90 percent of government revenue, in breach of the IMF/World Bank benchmarks.

Due to high level of indebtedness and limited access to concessional loans, the report said Nigeria has shifted its focus to the private creditors, whose loans constitute about 40 percent of the external debt stock, by providing high interest commercial loans through the Eurobonds and Diaspora Bonds.

“The concern is that this new frontier of lending (private creditors) operates to increase the cost of debt servicing, while restricting governments’ fiscal strength and constraining their ability to respond adequately to social and economic emergencies, including those brought to the fore by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic,” CISLAC’s Executive Director, Auwal Musa, said.

Since Nigeria can no longer access concessional loans, Musa said the government has diversified to borrowing from private creditors at ridiculous interest rates, pointing out that the real cost of the country’s debt mismanagement was the public services the country fails to get, the facilities and infrastructure lost and their impact on the people, women and children especially.

While provisions in the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) sets out fiscal discipline to checkmate the activities of the government officials, who have been shifting the Debt threshold from 20 percent to 40 percent, Musa said the country’s debt management strategy should be reviewed, such that the Fiscal Responsibility Commission (FRC) takes the responsibility of setting debt limits rather than the DMO, since they are the actual borrowers and have the responsibility of ensuring that interest rates for concessional loans should not exceed the statutory 3 percent.

“Debt limits should be set on revenues rather than using a vague concept. Most states are in debts, and it has become vital for states to first obtain a clean bill of health from the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) and the FRC before applying for loans.

“About 90% of government revenue is devoted to debt servicing at the expense of development projects. It is important that as a matter of urgency, we need to re-strategize as a country. Borrowed funds should be focused on self-liquidating projects that can pay back the loans, especially as debt servicing is a first-line charge, and therefore these agencies/private creditors give these loans with higher fiscal conditionalities,” he said.

The report underscored the need for the establishment of Debt Performance Auditing Mechanism in the face of rising sovereign debts, the changing landscape of creditors with the coming of private lenders and instruments, as well as the lack of adequate information on the terms and conditions and the various contingencies the sovereign debt is exposed to.

The mechanism, it said, would help to effectively monitor the impact of public debt on the country’s development as well as determine how debt is contributing to human security; monitor trends of risk and how to manage future borrowings to eliminate possible future crisis.

The level of opacity of loan terms and conditions in Nigeria, the report said, reinforces the need for a strong audit process and framework that allows for ascertaining the integrity of loan processes, to determine the sustainability level and risk management.

“There should be a regular audit of Nigeria’s sovereign debt by an independent body to track loan performance and impact,” the report said.

In addition, it identified the National Debt Management Framework, which provides a four years’ period as the basis for the auditing of the country’s debt, to ensure that government’s borrowing activities were conducted in accordance with the statutory provisions and regulations as well as international best practices.

The debt management framework, which reviews the external and domestic borrowing guidelines for the federal, states, FCT and their agencies to ensure conformity with the DMO strategic plan, includes the need to ensure the attainment of optimal debt composition of 60:40 ratio for domestic and external debt and 75:25 for long- and short-term debts, so as to reduce the cost of debt service and roll-over risks.

Besides, there must be a deliberate policy to ensure compliance with the provisions of Section 44 (4) of the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2007 which confers on the Fiscal Responsibility Commission the power to verify on a quarterly basis compliance by government agencies with the limits and conditions for borrowing by successive governments.